Modernization and The Middle Zone

“Functionalism undertakes to grapple with the effect of both the excessive primitiveness of underdevelopment regions and the excessive intricacy of economic and social relationships in the intensely industrialized parts of the world.” (Inis L. Claude, Swords into Plowshares. The Problems and Progress of International Organization)

“The functional approach plays an interesting role in this unstable and acrimonious relationship between liberalism and nationalism. While many of his liberal contemporaries felt threatened by nationalism, Mitrany recognized its importance. In doing so Mitrany demonstrated his twin intellectual debts – one to British liberalism and the other to his Balkan upbringing. Accepting the power of nationalism, Mitrany hoped to reconcile it with a liberal international order through his functional approach. His goal was not to diminish the force of nationalism in people’s lives, but to circumscribe its role so that it could not clash with liberal world-order goals.” (Lucian Ashworth, Bringing the Nation Back In? Mitrany and the Enjoyment of Nationalism)

David Mitrany, the scholar, was much more than the well-known IR theory author, the father of functionalism. Mitrany developed overtime a fascinating perspective combining social, economic, historical and geopolitical perspectives regarding Eastern Europe and what he called “The Middle Zone”:

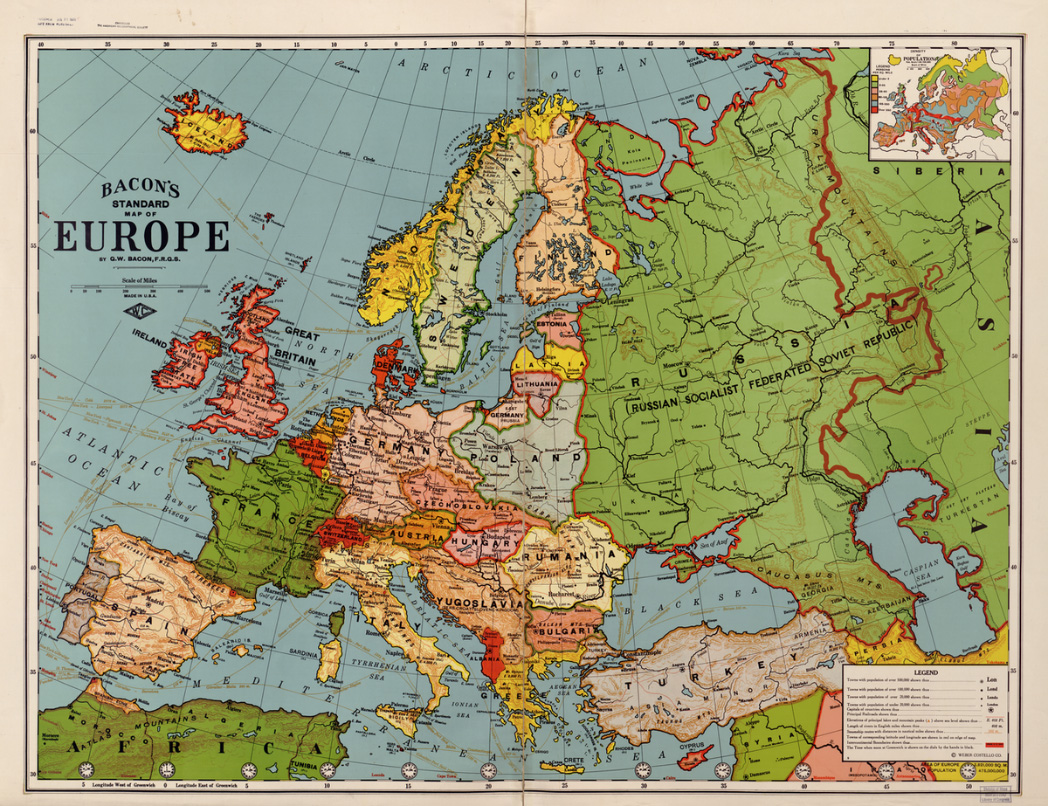

“There has always been a curtain somewhere along the line between the Baltic Sea and the Adriatic Sea. Sometimes it has been a curtain of iron or of diplomacy, sometimes of politics or of creeds and ideas. A strange region, with something of political witcheryin it. The Romans tried to get around it from the south, but after much trouble gave up the attempt. The Turks at the height of their power reached the line, but could not cross it. The fiery stream of western Protestantism did not get be-yond it, and the Eastern Church remained behind it…”

“Geographically it is a vague region, with no obvious characteristics or limits. The whole complex forms a system of contact and passage, which Halford Mackinder has aptly called lands of the overlap, which has made invasion from both east and west easy.”

Mitrany not only identified the region as a “area study” unit but also described and analyzed some of its features that give it a distinctive nature and role in the larger scheme of European and global geopolitics:

“The great admixture of peoples and religions and politics in the middle zone bears the mark of that porous geographical situation. It has made the fate of empires and even of small states uncertain. The middle zone remained politically in constant flux throughout the period of modern European consolidation, never attached solidly to any of the empires east or west or south. Before that, these territories and peoples had for centuries been caught in the workings of the balance of power; there was hardly one of them that had not at some time been marked for acquisition, partition, or compensation between the empires.”

The roots of present events in the middle zone are to be found, indeed, in the effect which the politics of the great powers, in their several phases, have had upon the internal life of these countries. Geography and history would in any case have made the region one almost to defy all modern principles of political organization; the policy of the powers has much aggravated those innate difficulties …

The point we have to retain explains Mitrany

…is the unsettling effect exercised by the position of the middle zone, and the in-ability of the ruling empires in that region to choose between an eastern and a western policy…at least, because this was a land of passage, no empire was willing to let another become established or predominant in the zone… It exposed the nations of the middle zone to endless political harrying, but it also had the effect of saving them from complete political extinction.

“An unstable political life was not propitious to the growth of a stable social life, let alone a progressive one. It has caused political differences between those countries and social problems within them to remain till our own day sore and feverish.”

Out of his analysis perhaps surprising but very well grounded and argued insights emerge:

“What a distortion of history it is to represent the Balkans as a spring of European conflict! The Balkan trouble seldom has been more than a rash when European politics were in fever. The Balkan problem has never been such a danger to European peace as European policy has been to the peace of the Balkans.”

A crucial contribution of the Mitrany’s perspective is the systematic connection that he makes between larger, macro level, structural political analysis and on the other hand, and, on the other hand, social and economic analysis focused on the micro level individual and household units. His work of peasant societies, the agrarian economies and their political and ideological implications and dimensions is a major (and yet largely unacknowledged) contribution to the social and political science literature of the 20st century. As Eduard Heimann put it:

“The setting of Mitrany’s story is, geographically, the area between the West, including Germany, and the Russian East; ideologically, between Marxist theory and Russian populism (the Narodniki, the Social Revolutionaries, and others). His theme includes the ideological struggle between Russian populism and Marxism before 1917 as well as the continuance of the struggle, with political and economic weapons, after that date. Russian populism, strictly opposed to Marxist collectivism, had developed an autonomous idea of agrarian socialism based on the traditional village cooperative and its far-reaching method of work-pooling.

Hence Mitrany’s story of modernization takes a different angle from the standard approaches to the region in this respect:

“[Mitrany puts at the center] the story of the peasant organizations and peasant parties which sprang up and came to power in the countries of Eastern Europe after the First World War, were submerged and silenced by the nationalist dictators of the interwar period—Pilsudski, Horthy, Carol, etc.—emerged again in the Second World War, and have now been broken by the maneuvers of the local Communist parties under the pressure of the liberating or occupying Soviet armies.

Nothing quite like these autonomous peasant movements… has ever been known in the urbanized, liberalized, intellectualized countries of Western and Central Europe, where social thinking is dominated by the categories of capital and labor, and conventional methods and assumptions give social science no access to facts outside a narrow range of problems considered “rational,” meaning an exclusive preoccupation with short-run technical efficiency and financial returns. From this point of view peasant movements appear “irrational” by definition, doomed either to be swept away automatically by man’s inherent drive to a reason-guided life, or to be deliberately done away with in order to make room for such a higher form of life. But if it is true that man lives on the goods he makes, it is no less true that he lives in making them” (Eduard Heimann).

Mitrany was thus more than the well known IR theory author, the father of functionalism. He was a pioneer in exploring the problem of the rural and peasant societies and economies in Eastern Europe, as confronted with the political and ideological trends of the 19 and 20th century. His focus on Agrarianism and Communism and the contention between the two is just one facet of his distinctive approach and analysis. The result is a unique perspective on the region, a fresh and surprising interpretation of the evolution of the states and nations of the area as confronted with the modernization process and the challenges of the 20th century:

“There was one aspect of that western neglect, if not hostility, which has played a special and vital part in the ultimate collapse of democracy in the middle zone-namely, the hostility of Socialists everywhere to the peasants. It had grown with the rise of Marxist socialism, which on dogmatic grounds decreed that the peasants were an anachronism and had to be rooted out as ruthlessly as the capitalists.”

“That division between the two sections of the working masses had already ruined the chances of the democratic revolution following 1918. But the Socialists never learned the lesson. In spite of their growing conflict with Communism, they continued everywhere to oppose the peasant outlook and claims, even to the point of collaborating against the peasants with some of the reactionary regimes of the middle zone. They continued to do so during the recent war, and in refuge; and after liberation they readily joined with the Communists in actions which were meant to block the revival of the Peasant movement, but which ultimately also destroyed the Socialists themselves.”

The ideas reflected in the codes quotations above are just the tip of the iceberg of the profound analysis developed by Mitrany in many of his works including: The Land and the Peasant in Romania: the War and Agrarian Reform, 1917-1921 (1930); The Effect of the War in South Eastern Europe (1936); Marx against the Peasant: a Study in Social Dogmatism (1951). Further exploring these ideas, recalibrating and testing their viability in the context of the developments of the 21st century is a source of a fascinating research agenda:

- ● Is the concept of “Middle Zone” relevant for the analysis of recent evolutions in the area?

- ● How should we interpret the current demographic social and cultural trends in the region, given the historical patterns and legacies noted by Mitrany’s interpretation?

- ● How should we address the social and structural legacies in the case of late modernizers in Eastern Europe?

- ● Is the predicament of the “Middle Zone” today changed by UE and NATO?

- ● How could Russia’s role be understood/reinterpreted through the lenses of the “Middle Zone” concept?

- ● How could the policy and strategy of the West be reassessed if we using the Mitrany’s conceptual tools? What are the trends in the region and how should be interpreted in the light of these lenses?

These and similar questions are at the core of the “Modernization and the middle zone” module of the research agenda of the Center.